Blame It On My Mother

My mother loves to travel near and far. Here we are wine tasting in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

By Regina Winkle-Bryan

Wanderlust? It runs in my family. I come from a long line of adventure-seekers. Then again, maybe the cause is more nurture than nature.

My mother is a traveler. I have often wondered if I would be as keen to globetrot had I not grown up with a mother who exposed me to a bigger world outside the small town I come from.

I blame my mother for my need to roam. For my curiosity. For my unconventionality.

Thank you, Mom.

Mom in Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain. She came often to visit me during the decade I lived there.

I do not ever remember saying as a child, “I want to do that. I want to travel.” Instead, it was a given. I knew I would see the world because that is what the women in my family do.

We are intrepid explorers.

My mother’s mother was born in the United States but lived in many countries. Pakistan, India, Iran, and the Philippines. She packed up her family’s belongings, her children, and a few cats and moved more times than she likely wanted to.

I do not think my grandmother would have called herself an adventure-seeker. But she chose an unconventional path when she married my grandfather, who was a writer and arrived at their wedding by illegally hopping trains across the United States.

Abroad, my grandmother embraced the expat lifestyle. She made friends everywhere she went. Every Christmas for the rest of her life, cards with stamps from far-flung locales filled her mailbox.

Her travels changed her life. In Bangalore, my grandmother taught English to nurses, kicking off a 26-year career as a college ESL teacher. This was long before teaching English was a mainstream gig for restless twenty-somethings.

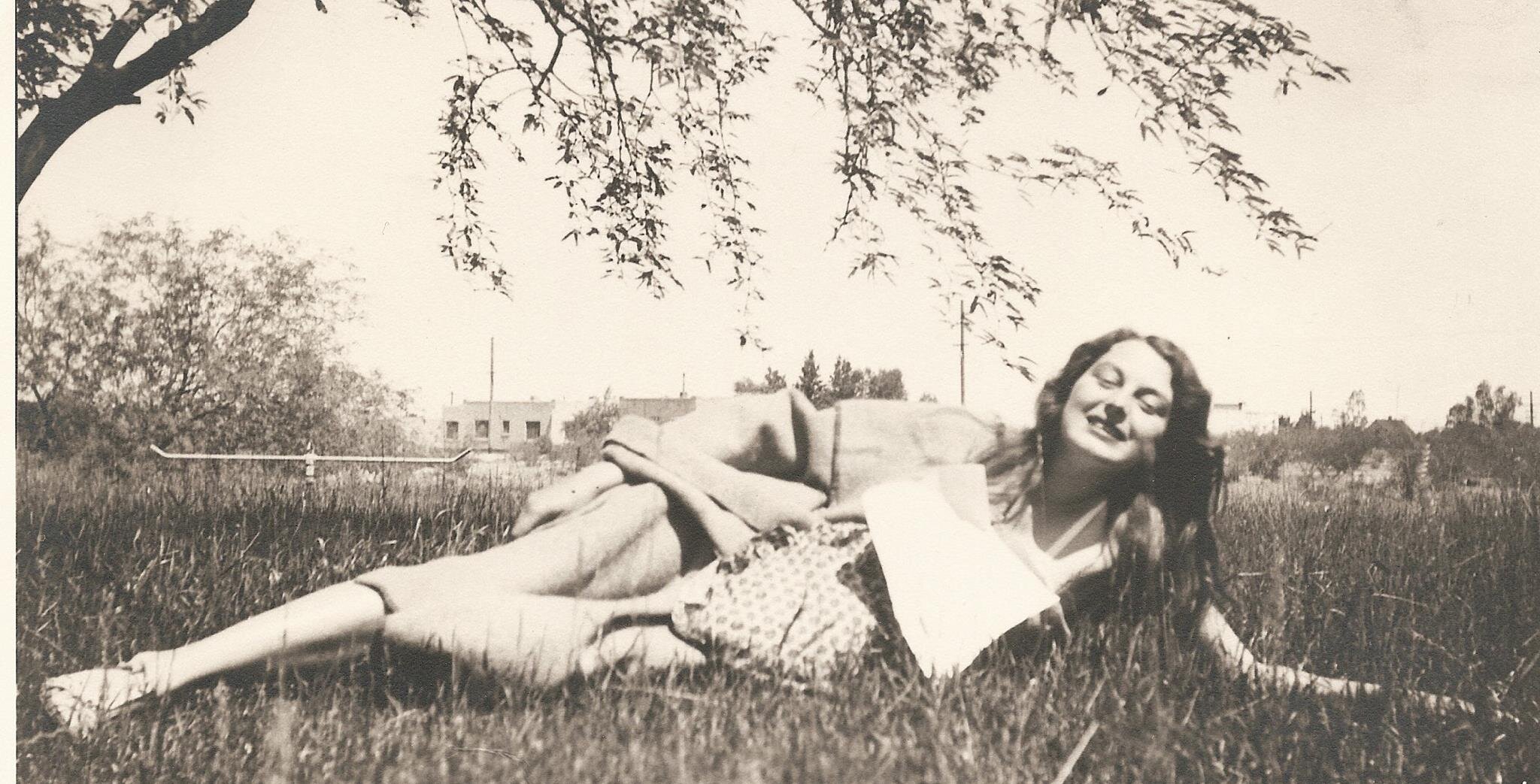

My grandmother the expat explorer. A bold woman if ever there was one.

Imagine her for a moment. My grandmother, buying meat at the crowded market in Tehran. At 5’11”, she stands out. She haggles. She is a foreigner in a noisy bazaar filled with men. This is a bold woman.

When she and my grandfather eventually returned to the United States, they unpacked one last time, exotic souvenirs tumbling forth from their luggage. Carved tables from India. Tea trays from Iran. Camel saddles repurposed as ottomans. Intricate rugs from the Middle East. I stared at these objects for hours, imagining what it might be like to ride a camel.

My grandmother lived in many exotic locations, including Iran. Photo by Mehrshad Rajabi.

I want to tell you what my mother did when she was about to turn 50. She packed her bags and went to Kenya, alone. She met up with some other NGO volunteers and lived in a hut made of mud. She ate goat and ugali, an African corn flour porridge. She stayed for five weeks. The locals called her “Mama Safi,” or Clean Mama, because she was always tidying up.

Then, she went on safari with a local guide and his son—just the three of them out there in the wild. She saw those majestic grassland creatures in their natural habitat: powerful herds of elephants, wildebeests, giraffe, and warthog.

Travel changed my mother’s professional life, just like it changed my grandmother’s. After returning from Africa, she became a social worker and has been working in the field ever since.

My mother in Africa on safari. She has never been afraid to travel alone.

The first time I lived overseas, I chose Costa Rica as part of a study abroad program. I was twenty. Some parents might have tried to dissuade their child from taking off to Central America, but not my mother. I think she missed me, but she also had an excuse to buy plane tickets. She was the first to visit me there. We rode horses, hiked through the cloud forest, beach-combed along the Pacific Ocean, and soaked in hot springs together.

She is not afraid of tropical bugs and dirt, my mother. She is not afraid of getting lost or not knowing the language. She is afraid of not living life to its fullest. She is afraid of wasting this brief moment we have together on Earth.

I am afraid of these same things.

My mother and I traveled across Costa Rica together when I was twenty. Photo by Etienne Delorieux.

When I hopped from Costa Rica to the colonial streets of Antigua, Guatemala, my mother came to see me. She stayed for a month, working during the day teaching art to children at Camino Seguro, an organization that helps impoverished children.

When, a few years later, I swapped Guatemala for Spain, my mother promptly arrived. We explored big-city Barcelona and Granada’s Alhambra together. But this was not my mother’s first trip to Spain. She had come not long after dictator Francisco Franco’s death.

I can easily visualize my mother strolling along the grand boulevards of Madrid because I have walked those same streets.

My young mother, unknowingly eating lamb brain, blood sausage, and tripe prepared by her Spanish hostess. My mother, learning Castilian. My mother flirting in bars and making new friends.

This was the tail-end of the ‘70s. She spent six months on trains discovering Europe at her own pace. She was alone, but I don’t think she was lonely.

I lived in Guatemala for a couple of years. My mother came to visit and taught art at Camino Seguro. Photo by Clovis Castaneda.

I do not mind traveling alone. Sometimes, I even prefer it. But whenever I can, I travel with my mother. We are great road buddies. Never sit next to us on an airplane—we talk incessantly. We laugh loudly from the belly.

There is a photograph of me at the airport taken quite a while back. I am just twenty. I have on faded jeans and a raincoat. My hair is in two long braids. A backpack sits across my shoulders.

I am nervous but smiling. I am young, and brave, and free.

I look just like my mother.